Introduction

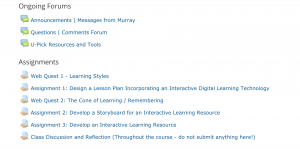

For students participating in online courses, the design of a course, including its attention to student needs, ease of use, and methods of interaction, influence its overall effectiveness. Over the past two semesters, I have transitioned from in-person to online education, and have participated in several online courses. One of my most positive online learning experiences was in UVIC’s EDCI335 – Learning Design, which showed clear awareness of many aspects of Bates’ (2019) SECTIONS model (Chapter 9). This created a rich and meaningful learning experience. Below I will analyze this course in accordance with each aspect of the SECTIONS model, identifying key strengths and potential areas for improvement.

Image 1 – SECTIONS Model

Figure 9.1.1 The SECTIONS model by Bates is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Analysis using the SECTIONS Model

Students

As stated by Bates (2019), “the first step in media selection is to know your students” (section 9.2.3); that is, their similarities, differences, access to technology, interests, and needs. Given that EDCI335 was a mandatory course for UVIC’s Personalized Learning Institute (PLI), the professor had some initial information about the learner demographic. For example, most students were educators in some capacity and knew each other from the in-person summer learning institute. Knowledge of these factors likely assisted with course design. Additionally, each student wrote an introductory forum post with their current teaching position, passions, hobbies, and goals for the course. This additional step enabled the professor to gain a better grasp of his student demographic, thus allowing for adjustments to be made as necessary.

Alongside the importance of knowing who you are teaching in an online setting, Bates (2019) suggests that for any online course it is important to consider that “different students will have different preferences for different kinds of technology or media” (section 9.2.3). This concept further aligns with the Inclusive Design principles which encourage creators to be mindful of student diversity and uniqueness (OCAD University, 2018). Student preferences were addressed in EDCI335 by offering a variety of exploratory media resources (images, videos, articles, blogs, etc.) during each bi-weekly module which students used to self-direct research and discover given topics. Providing this aspect of choice was a manageable way to meet a diverse range of students learning preferences.

One possible oversight in regards to student-specific considerations was that there were no clear guidelines around the prerequisite skills or required technologies needed for this course (UVIC, 2019). Thus, students could have joined the course without having the skills or equipment needed to fully participate and be successful, creating a potential disadvantage to some. This challenge could easily be resolved by including these criteria in the course description.

Ease of Use

This course was “well structured, intuitive for the user to use, and easy to navigate (Bates, 2019, section 9.3.4).” This was achieved through a simple course interface and basic digital layout on UVIC’s Learning Management System CourseSpaces (UVIC, 2018). On the CourseSpaces page, major assignments and semester-long forums were posted at the top, and additional resources and assignments were split into bi-weekly modules listed sequentially below (see images below). This format was likely familiar to students who had previously taken online courses through UVIC. For new students, it was concisely explained in a 10-minute video tutorial.

Image 2 – Top of the CourseSpaces page (ongoing resources)

*Click here to enlarge image

Image 3 – Example of a bi-weekly module

*Click here to enlarge image

Screenshots of EDCI 335 CourseSpaces Page (Richmond, 2020)

Cost

Aside from the tuition cost, which was consistent with other UVIC online courses, the professor utilized free online sources and technologies to minimize student costs. Furthermore, access to CourseSpaces is granted to all students and faculty “free of charge” (UVIC, 2018).

Teaching and Pedagogical Factors

As outlined by Bate’s (2019) and Crosslin (2018), there are many features that contribute to good online courses. In his list of best practices, Crosslin (2018) includes a focus on active engagement and instructor participation (chapter 5). As seen in Image 3 – Example of a bi-weekly module, every module of EDCI335 had a learning activities page that contained a variety of multimedia resources, as well as an interactive learning task such as a small assignment, forum discussion prompts, or a project. This component greatly enhanced active student engagement. Furthermore, the professor also participated alongside students commenting on forums, providing feedback on assignments, and posting helpful tips and tricks. This format made it apparent that the professor believed in a connectivist approach to learning, in which he and the students worked together to develop understanding, rather than an instructivist approach, in which he would merely impart knowledge (Crosslin, 2018, Chapter 2). This approach recognized the worth of each students’ personal knowledge and experiences as an educator. In turn, this made the students willing and excited to engage. With regard to media selection, it was apparent that the professor was constantly considering the effective multimedia principles that Bate’s discusses in section 9.5.1 of his article. Resources were simple and coherent, included multiple modalities (i.e. pictures, videos, and text), and were relatable and personalized to the students’ context as teachers (i.e. teaching blogs, relevant educational news articles, etc.).

Interaction

A key component to online course design is deciding if and how students will interact with one another. This course was primarily asynchronous, meaning it did “not require learners to meet in the same space at the same time” (Crosslin, 2018, Chapter 2), which was ideal for participants who were primarily working professionals and required flexibility. However, after some students shared that they would like opportunities to connect synchronously, regular Blue Jeans conference sessions were also included which allowed students to discuss course content and questions synchronously. In the future, this is an adjustment that could be integrated from the beginning of the course to increase interaction. Alternatively, Flipgrid could be used to allow students to have ‘face-to-face’ conversations, in an asynchronous manner as well.

In the SECTIONS model, another “key decision for a teacher or course designer is choosing the best mix of […] different kinds of interaction” (Bates, 2019, section 9.6.1). Within EDCI335, there were structures in place which allowed for variety in interaction types. Interaction with materials was supported via regular forum posts which required the integration of various sources. Frequent student-teacher interactions occurred through email communication and forum comments, while student-student interaction was encouraged through forum responses and optional group work.

Organizational Issues

UVIC, as an institution, is well equipped to offer online courses. This course took advantage of the standard setup UVIC offers, which includes a CourseSpaces page, class forums, assignment submission areas, etc. Seeing as most of the learners in this class had taken other courses through UVIC, this choice in platform seemed logical. However, in his SECTIONS model, Bate’s does identify that educators “often [have] a bias towards those technologies that can be introduced with the minimum of organizational change, although these may not be the technologies that would have maximum impact on learning” (2019, section 9.7.1). While this could be true, I do think this standard format was a logical choice as most of the students in this class did not have free time to explore a new platform. A more complex platform, even if more ideal, may have hindered learning more than helping it.

Networking and Novelty

Unfortunately, networking was one area that this course paid little attention to. Although classmates connected with one another via forum comments, there was little encouragement to connect outside of the class with peers or other community members (i.e. colleagues, Personal Learning Networks, etc.). It is unclear if this was intentional or not; however, as education is a highly collaborative field, encouraging networking is another potential area for improvement. More specifically, there could be added encouragement to share projects on social media or to get connected with a Personalized Learning Network (PLN).

Security and Privacy

The decision to use CourseSpaces was not only a good decision for its ease of use, low costs, and student familiarity; it also ensured that all students’ data would be kept private. In the future, if social networking opportunities were to be encouraged in this course, additional privacy considerations may need to be made. For example, students could use pseudonyms or create professional accounts. In addition, suitable alternatives for students who do not wish to share personal information outside of the course would be required.

Image 4 – Summary Mind Map

Click here to enlarge image

Concluding Thoughts

This essay outlines some of the many strengths of UVIC’s EDCI335 course as well as a few potential areas for growth. Some of the positive features include consideration of, and personalization to, student diversity; clear and concise layout; ease of use; and encouraging student interaction. Despite all of these positive attributes, online courses should always seek improvement. Some potential ideas to improve learning include: listing pre-requisite requirements in the course description; adding additional video response platforms; and encouraging student networking beyond the course. Overall, I found that the vast number of positive attributes of UVIC’s EDCI 335 far outweighed its potential shortcomings, making it a course I would highly recommend to others.

References

Bates, A. W. (2019). Teaching in a Digital Age (Second Edition). Retrieved from https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev2/

Crosslin, M. (2018). Creating Online Learning Experiences. Retrieved from https://uta.pressbooks.pub/onlinelearning/

OCAD University. (2018). What do we mean by Inclusive Design? Retrieved from https://idrc.ocadu.ca/index.php/resources/idrc-online/library-of-papers/443-whatisinclusivedesign

Richmond, M. (2020). CourseSpaces Screenshots [Digital image]. Retrieved from EDCI 335 CourseSpaces page

UVIC. (2018). Learning Management System: CourseSpaces [Webpage]. Retrieved https://www.uvic.ca/systems/services/learningteaching/coursespaces/index.php

UVIC. (2019). EDCI 335: Learning Design [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://web.uvic.ca/calendar2020-01/CDs/EDCI/335.html